Tearing Down The Wall

By Jodi Becker Kinner

Written in 2000

Posted in 2016

Updated in 2022

If you are not willing to learn, no one can help you.

If you are determined to learn, no one can stop you. ~ Anonymous.

NOTE

As a Deaf person growing up in an oral environment, I would like to clarify that the purpose of this article is not to focus on the effects of early language deprivation or limited exposure to early language acquisition. Although I fully support deaf and hard of hearing children's early language development, this is a separate issue. True, the linguistic deprivation I experienced at home had an impact on my learning progress (I did not learn American Sign Language until I was in college). However, the objective of this story is to focus on my cognitive process, which is associated with visual processing disorder and slow processing issues. I was diagnosed with learning disabilities in a visual-motor processing and visual-spatial issues, as well as slow processing speed, twice in high school and once in college. Despite the language-rich environment provided in our home, as a Deaf parent of two Deaf children (a son and a daughter), I have observed some similar patterns in my daughter and would like to share my story with you.

Jodi Becker Kinner, 2021

Jodi Becker Kinner, 2021

I'd like to share my experience with "Tearing Down the Wall." After finishing my Master's degree at Gallaudet University in 2000, I was on my way to Utah to see my parents at Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. My parents and I were talking about the history of my academic difficulties over dinner. My mother explained "The Wall" and how it affected my learning performance. I had a long period of reflection while traveling to Utah. Since then, I've come to understand why I built "The Wall" in the first place and how I used it to avoid learning.

First and foremost, I am a Deaf adult with a learning disability that includes a visual-motor processing disorder/visual-spatial disorder and a slow processing speed. Throughout my early childhood, my well-educated parents (hearing) attempted to teach me about life, subject matter, and a love of books. However, because learning was so difficult for me, I built "the wall" around myself. When I first started developing learning strategies, the process was extremely difficult, and I became extremely frustrated. To avoid frustration, I built this wall around myself. It relieved my frustration and temporarily relieved me of my learning difficulties. Not only that, but I clung to the wall to escape my frustration with academic challenges and, at times, with life in general.

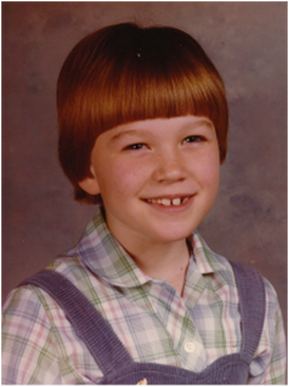

Please allow me to share my educational background and how learning has affected me mentally, emotionally, and psychically before explaining how my learning disability was diagnosed. As an Air Force brat, I attended school in a variety of oral education and mainstreamed settings. I started formal school at the Omaha Hearing School (deaf oral school) in Omaha, Nebraska, when I was three years old. My parents reported that I enjoyed and looked forward to going to school because my teachers incorporated a lot of physical activity into the language acquisition activities. Two years later, I enrolled at the Central Institute for the Deaf (CID) in St. Louis, Missouri, where I spent nine years. This, as far as I recall, was the beginning of my disinterest in school. I struggled with reading, handwriting, spelling, math, and organizational skills. The challenges became more difficult to overcome with each passing year. In addition to intensive speech and language skills every day, I studied reading, English, mathematics, history, science, and other subjects. With my visual-spatial disorder and slow processing issues, my daily academic struggles frustrated me, and I grew up disliking school. At CID, I built "the wall" higher and higher over the years. When I was in school, I clung to "the wall" to keep myself from learning and to avoid frustration.

First and foremost, I am a Deaf adult with a learning disability that includes a visual-motor processing disorder/visual-spatial disorder and a slow processing speed. Throughout my early childhood, my well-educated parents (hearing) attempted to teach me about life, subject matter, and a love of books. However, because learning was so difficult for me, I built "the wall" around myself. When I first started developing learning strategies, the process was extremely difficult, and I became extremely frustrated. To avoid frustration, I built this wall around myself. It relieved my frustration and temporarily relieved me of my learning difficulties. Not only that, but I clung to the wall to escape my frustration with academic challenges and, at times, with life in general.

Please allow me to share my educational background and how learning has affected me mentally, emotionally, and psychically before explaining how my learning disability was diagnosed. As an Air Force brat, I attended school in a variety of oral education and mainstreamed settings. I started formal school at the Omaha Hearing School (deaf oral school) in Omaha, Nebraska, when I was three years old. My parents reported that I enjoyed and looked forward to going to school because my teachers incorporated a lot of physical activity into the language acquisition activities. Two years later, I enrolled at the Central Institute for the Deaf (CID) in St. Louis, Missouri, where I spent nine years. This, as far as I recall, was the beginning of my disinterest in school. I struggled with reading, handwriting, spelling, math, and organizational skills. The challenges became more difficult to overcome with each passing year. In addition to intensive speech and language skills every day, I studied reading, English, mathematics, history, science, and other subjects. With my visual-spatial disorder and slow processing issues, my daily academic struggles frustrated me, and I grew up disliking school. At CID, I built "the wall" higher and higher over the years. When I was in school, I clung to "the wall" to keep myself from learning and to avoid frustration.

Difficulty Processing the Visual Information

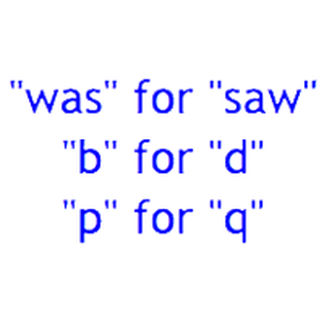

Word/Letter Reversal. @http://drnewmanoptometry.com

Word/Letter Reversal. @http://drnewmanoptometry.com

Looking back, I remember having academic difficulties in school for many years. I became easily distracted as the pages were covered with new information and symbols due to my difficulty processing visual information. I either ignored or avoided the visual tasks. My math skills were poor in school, and I struggled to solve math problems correctly. I had difficulty comprehending and organizing mathematical concepts. I even missed function signs and skipped steps. I was also confused by formulas that appeared to be visually similar. When it came to reading, I was easily distracted by too much visual information. I had trouble organizing words that appeared jumbled on the page. When reading, I would skip words or entire lines, and I would sometimes read the same sentence over and over. I had difficulty recalling visual information when reading textbooks. In college, I had to take notes to help me remember what I had just learned, or I would forget.

Reading cluttered menus and recipes was another difficult task for me. It was especially difficult to navigate the clutter of words and symbols and choose an item from the menu. It was nearly impossible to decipher the jumble of words found in recipes. It took me an inordinate amount of time to learn and differentiate between the various types of food available on the menu and in recipes. It was often overwhelming. I couldn't read and follow the instructions in cookbooks, especially the measurement concepts. The instructions appeared to be crammed into small paragraphs with small print. especially difficult to navigate the clutter of words and symbols and choose an item from the menu. It was nearly impossible to decipher the jumble of words found in recipes. It took me an inordinate amount of time to learn and differentiate between the various types of food available on the menu and in recipes. To understand the instructions, I had to break them down into small steps that I could follow before I could even start cooking a meal. It was extremely time-consuming, and I lacked the patience for it. These experiences most likely contributed to my reluctance to learn to cook, despite my mother's efforts to teach me.

I had difficulty spelling familiar words with irregular spelling patterns, such as their/there, recipe/receipt, and quiet/quite. I made numerous spelling mistakes. Worst of all, I remember not knowing where to put a period at the end of each sentence. While doing schoolwork or taking notes from the board, I frequently reversed or misread letters, numbers, and words. I frequently got two words that should be together reversed, such as "Babel of Tower" instead of "Tower of Babel." Furthermore, I had difficulty distinguishing between similar-looking letters and numbers on worksheets such as d/b, p/q, h/n, m/w, and 6/9. I had trouble following directions or instructions that required visual organization. My handwriting was/is terrible, and it's difficult to read what I've written at times. I can't write cursive and can't read cursive writing very well (thank goodness for computers!).

Participating in a team sport like basketball, volleyball, or soccer was out of the question. My visual-spatial disorder not only affected how I learned, but it also affected my spatial ability to play sports.

Reading cluttered menus and recipes was another difficult task for me. It was especially difficult to navigate the clutter of words and symbols and choose an item from the menu. It was nearly impossible to decipher the jumble of words found in recipes. It took me an inordinate amount of time to learn and differentiate between the various types of food available on the menu and in recipes. It was often overwhelming. I couldn't read and follow the instructions in cookbooks, especially the measurement concepts. The instructions appeared to be crammed into small paragraphs with small print. especially difficult to navigate the clutter of words and symbols and choose an item from the menu. It was nearly impossible to decipher the jumble of words found in recipes. It took me an inordinate amount of time to learn and differentiate between the various types of food available on the menu and in recipes. To understand the instructions, I had to break them down into small steps that I could follow before I could even start cooking a meal. It was extremely time-consuming, and I lacked the patience for it. These experiences most likely contributed to my reluctance to learn to cook, despite my mother's efforts to teach me.

I had difficulty spelling familiar words with irregular spelling patterns, such as their/there, recipe/receipt, and quiet/quite. I made numerous spelling mistakes. Worst of all, I remember not knowing where to put a period at the end of each sentence. While doing schoolwork or taking notes from the board, I frequently reversed or misread letters, numbers, and words. I frequently got two words that should be together reversed, such as "Babel of Tower" instead of "Tower of Babel." Furthermore, I had difficulty distinguishing between similar-looking letters and numbers on worksheets such as d/b, p/q, h/n, m/w, and 6/9. I had trouble following directions or instructions that required visual organization. My handwriting was/is terrible, and it's difficult to read what I've written at times. I can't write cursive and can't read cursive writing very well (thank goodness for computers!).

Participating in a team sport like basketball, volleyball, or soccer was out of the question. My visual-spatial disorder not only affected how I learned, but it also affected my spatial ability to play sports.

Confused with directions. www.ldresources.org

Confused with directions. www.ldresources.org

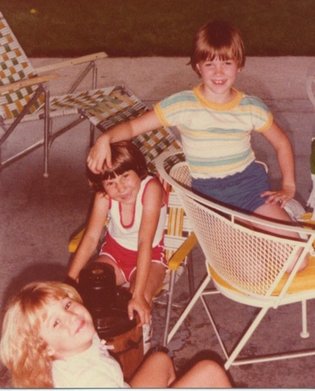

I was always confused by the concept of left and right. My younger hearing sister, Jami, whom I called "the brain and beauty," noticed that I was frequently confused by it and decided to help me distinguish between left and right. "Which hand do you write with?" she asked. After a few moments of thought, I replied, "Right." "Exactly," she said. This has stayed with me since. Whenever I was confused by directions, I would recall which hand I write with and begin to figure out how to get to a specific location I was looking for. Even today, Duane, who comes from a Deaf family, would sign the spatial location of objects because American Sign Language is a spatial language. I'd ask him, confused and lost, "Left or right?" He usually sighs and responds with "left" or "right."

When I was ten years old, I flew to Canada by myself to see my friend Arista Hass, who lived with us while attending Central Institute for the Deaf. As an illiterate about to land at Edmonton International Airport, I couldn't understand the flight attendant's written instructions. I couldn't even understand his lipreading. I simply smiled and nodded. As soon as I stepped off the plane, I was overwhelmed and disoriented, unable to find my way or read the signs. I went completely still! Fortunately, another flight attendant came to my aid and directed me to Arista and her parents, Peter and Helen, at the far-flung gate. It was probably the worst nightmare I'd ever had, and certainly the most bizarre. In retrospect, being illiterate with a visual spatial disorder can be quite frightening!

These aspects of my academic difficulties made it difficult for me to do well in school. I clung to the wall, preventing me from learning while also attempting to escape frustration. Because of my difficulty processing visual information (especially when it comes at me rapidly and distractions are present) and recalling what I had learned, it became clear that I needed more time to learn new material. I also needed time to become familiar with unfamiliar situations before progressing to the next level and adjusting to the new situation. It was by no means an easy process!

When I was ten years old, I flew to Canada by myself to see my friend Arista Hass, who lived with us while attending Central Institute for the Deaf. As an illiterate about to land at Edmonton International Airport, I couldn't understand the flight attendant's written instructions. I couldn't even understand his lipreading. I simply smiled and nodded. As soon as I stepped off the plane, I was overwhelmed and disoriented, unable to find my way or read the signs. I went completely still! Fortunately, another flight attendant came to my aid and directed me to Arista and her parents, Peter and Helen, at the far-flung gate. It was probably the worst nightmare I'd ever had, and certainly the most bizarre. In retrospect, being illiterate with a visual spatial disorder can be quite frightening!

These aspects of my academic difficulties made it difficult for me to do well in school. I clung to the wall, preventing me from learning while also attempting to escape frustration. Because of my difficulty processing visual information (especially when it comes at me rapidly and distractions are present) and recalling what I had learned, it became clear that I needed more time to learn new material. I also needed time to become familiar with unfamiliar situations before progressing to the next level and adjusting to the new situation. It was by no means an easy process!

Suspecting Learning Disability

Jami, Arista & Jodi making ice cream, 1981

Jami, Arista & Jodi making ice cream, 1981

My mother, who majored in special education, suspected I had a learning disability when I was seven years old because of my academic delays at the Central Institute for the Deaf. She noticed that I was not progressing academically as well as other students (Their literacy skills exceeded their oral communication skills). I didn't start reading until I was ten years old. Because of my slow processing issues, my reading speed was extremely slow. I had difficulty recognizing and remembering what I had just read. I was easily frustrated by reading activities. As previously stated, I struggled to understand what I was reading. When reading, I had trouble recognizing variations of learned words that included past tense markers, plural markers, and capital letters. For example, if I learned to read sight words like "walk," "house," and "the," I would not recognize the words "walked," "houses," or "the" automatically. This hampered my reading because I couldn't make out the printed symbol. In terms of writing, I had trouble organizing my work on paper and recalling written sequences. When I was writing, my processing speed was slow, and it took time to process and organize my thoughts and feelings. Writing was a time-consuming and laborious task. In college, I had to work on papers well ahead of the official due dates. My vocabulary was extremely limited. I struggled with new words; they didn't seem to stick around for long. It was difficult to memorize new words. Preparing for tests was time-consuming and exhausting. As a result, reading, writing, and learning vocabulary took a lot of time.

Inspired by the "Anne of Green Gables" Book

Anne of Green Gable

Anne of Green Gable

Due to my lack of visual discrimination skills, I had difficulty noticing similarities and differences between objects, particularly food. I couldn't tell the difference between a zucchini/cucumber and a sweet potato/yam, for example. Let's fast forward to the real world. I'd go to the grocery store and buy the wrong vegetable. I intended to buy a zucchini. Instead, I'd bring a cucumber home. My husband, Duane, immediately recognized the difference and would tell me that I had made a mistake! Lesson learned. I learned then that I needed to read the labels instead of just looking at the vegetables and assuming they were the right ones. Back at CID, I was pulled out of recess to learn to identify the various types of food depicted in the pictures because I needed extra assistance learning new things. It was a very unpleasant experience. My attitude toward school remained negative until I was thirteen. Heather Whitestone, a CID friend who went on to become Miss America, encouraged me to read Anne of Green Gables, her favorite book. I tried, but I couldn't understand the words. Instead, I watched the movie with captions and fell in love with the main character, Anne Shirley, who inspired me to use my imagination and enjoy learning. My desire to further my education had started. However, academic struggles had taken a toll. I realized I couldn't use the wall to avoid learning anymore. To begin my true learning, I had to break down the wall and learn how to deal with my frustration and learning challenges.

Paralyze Under Pressure

Jodi Becker, Blanca Gonzalez, Heather Whitestone, 1987

Jodi Becker, Blanca Gonzalez, Heather Whitestone, 1987

We, the students, were due to take the annual standard school achievement tests shortly before I graduated from CID in May 1987. These tests were used to assess students' academic achievement over the course of a single academic year. I was unable to complete the tests in the allotted time because they were timed. Under the pressure, I became paralyzed, and my mind became completely blocked. Because I was frustrated, I gripped the wall even tighter.

For the first time in years, I became aware that I was not completing the tests as quickly as my peers. When the timer went off, the teacher collected our papers. I felt stupid for not finishing the test in the allotted time. I couldn't figure out why I couldn't finish it in the allotted time. I felt embarrassed. "I wasn't able to finish the test," I explained shyly as I handed my test to the teacher. She looked concerned as she examined my test. "It's okay," she said, "we'll figure it out."

A few days later, the teacher arranged for me to take tests with extra time in the assistant principal's office. Surprisingly, at my own pace and for the first time, I was able to better understand the test questions and progress through them without feeling stressed or rushed. As soon as I finished the test, I realized that I didn't need to cling to the wall to relieve my frustration. CID sent me a letter a few days later, saying that I had made more than a year's progress on my standard school achievement test. It was decided that I would be able to graduate from CID one year early. Some of my friends were surprised because they thought I wasn't smart enough to graduate early. It was the first time I became aware of the criticism I received from others. I was aware that I was falling behind academically, but the word "smart" just popped into my head. Maybe they were right about me not being as smart as them. I grew up with most of my friends who were gifted and, unlike me, excelled in school. My friends' perception of my intellectual ability deeply hurt me. My desire to become smarter and to obtain an education had grown.

For the first time in years, I became aware that I was not completing the tests as quickly as my peers. When the timer went off, the teacher collected our papers. I felt stupid for not finishing the test in the allotted time. I couldn't figure out why I couldn't finish it in the allotted time. I felt embarrassed. "I wasn't able to finish the test," I explained shyly as I handed my test to the teacher. She looked concerned as she examined my test. "It's okay," she said, "we'll figure it out."

A few days later, the teacher arranged for me to take tests with extra time in the assistant principal's office. Surprisingly, at my own pace and for the first time, I was able to better understand the test questions and progress through them without feeling stressed or rushed. As soon as I finished the test, I realized that I didn't need to cling to the wall to relieve my frustration. CID sent me a letter a few days later, saying that I had made more than a year's progress on my standard school achievement test. It was decided that I would be able to graduate from CID one year early. Some of my friends were surprised because they thought I wasn't smart enough to graduate early. It was the first time I became aware of the criticism I received from others. I was aware that I was falling behind academically, but the word "smart" just popped into my head. Maybe they were right about me not being as smart as them. I grew up with most of my friends who were gifted and, unlike me, excelled in school. My friends' perception of my intellectual ability deeply hurt me. My desire to become smarter and to obtain an education had grown.

My First Time Mainstreamed

Literary Analysis. Published by Pierce Howard

Literary Analysis. Published by Pierce Howard

After graduating from the Central Institute for the Deaf in 1987, I attended Goodwyn Junior High School in Montgomery, Alabama, for one year. I started seventh grade there and was placed in a deaf program with other deaf and hard of hearing students, as well as physical education with hearing students. When I first started at that school, I had to learn how to break down the "wall." I struggled academically and studied for extended periods of time. I was able to maintain good grades and make the honor roll with the help of my teacher and parents. I was also chosen for the Miss Goodwyn Pageant, which was a life-changing experience for me.

I skipped eighth grade due to my age when my father, who was in the Air Force, was stationed at the Pentagon in Springfield, Virginia, in 1988, and spent my freshman and sophomore years at Annandale High School, where I still struggled academically. For the first time, I was mainstreamed during my freshman year. I only took self-contained math and English classes. I had a conflict with one of my Deaf Education teachers, with whom I shared self-contained math and English classes. I struggled with fractions, decimals, and percentages in math class. I frequently had to recall simple math facts. I was always making mistakes, and my numbers were frequently reversed when I copied from a textbook or the blackboard. I struggled to organize mathematical problems and complete my assignments correctly. To keep columns aligned in written math assignments, I had to use graph paper. Graphing assisted me in organizing the problems, but it did not always assist me in avoiding errors. I couldn't find and correct simple math mistakes. Despite the one-on-one, slow-paced instruction I received in English, I struggled with reading comprehension and writing organization. I had trouble reading look-alike words like "hat" and "hot," as well as words with similar shapes like "boy" and "dog." I worked hard and studied for long hours, but despite my efforts, I performed poorly in some classes.

I skipped eighth grade due to my age when my father, who was in the Air Force, was stationed at the Pentagon in Springfield, Virginia, in 1988, and spent my freshman and sophomore years at Annandale High School, where I still struggled academically. For the first time, I was mainstreamed during my freshman year. I only took self-contained math and English classes. I had a conflict with one of my Deaf Education teachers, with whom I shared self-contained math and English classes. I struggled with fractions, decimals, and percentages in math class. I frequently had to recall simple math facts. I was always making mistakes, and my numbers were frequently reversed when I copied from a textbook or the blackboard. I struggled to organize mathematical problems and complete my assignments correctly. To keep columns aligned in written math assignments, I had to use graph paper. Graphing assisted me in organizing the problems, but it did not always assist me in avoiding errors. I couldn't find and correct simple math mistakes. Despite the one-on-one, slow-paced instruction I received in English, I struggled with reading comprehension and writing organization. I had trouble reading look-alike words like "hat" and "hot," as well as words with similar shapes like "boy" and "dog." I worked hard and studied for long hours, but despite my efforts, I performed poorly in some classes.

An Official Diagnosis

At the end of the school year in 1989, I was given a psychological evaluation test and was diagnosed with a learning disability in visual-motor integration disorder. According to the evaluation, my scores showed a significant disparity between my ability and achievement in math and written expression. In addition, I demonstrated functional deficits in visual-motor integration. My perceptual-motor integration deficits hampered my ability to read instructions accurately and resulted in letter and digit reversals while writing or copying. Furthermore, my diagnosis revealed that my visual-motor integration deficits had hampered my early learning development and had a significant impact on my academic potential.

I'd never heard of this diagnosis before and was reluctant to accept the report. It was administered by a psychologist with little knowledge of deafness. I refused to follow his advice and felt I was mislabeled as a result of my academic failure. I also believed that my literacy skills were delayed due to my lack of exposure to early language and that they were related to my deafness rather than a learning disability. Despite the fact that the test results confirmed what I already suspected: that I had a limited vocabulary, severe problems with reading comprehension, poor writing skills, poor grammar, poor organization, and math problems, I was not ready to accept the fact that I had a learning disability.

I'd never heard of this diagnosis before and was reluctant to accept the report. It was administered by a psychologist with little knowledge of deafness. I refused to follow his advice and felt I was mislabeled as a result of my academic failure. I also believed that my literacy skills were delayed due to my lack of exposure to early language and that they were related to my deafness rather than a learning disability. Despite the fact that the test results confirmed what I already suspected: that I had a limited vocabulary, severe problems with reading comprehension, poor writing skills, poor grammar, poor organization, and math problems, I was not ready to accept the fact that I had a learning disability.

Feeling Stupid and Isolated

During my sophomore year, I was assigned to resource classes for students with learning disabilities as well as deaf classes for deaf and hard of hearing students. I was astounded to see how the students behaved in the classroom, particularly how they treated the teacher, in the resource classes. Some of their actions were disrespectful.

They did not adhere to classroom norms. During lectures, one of the students would usually get up and walk to the window to look out. Another student would lean back and gaze at the ceiling. Some of them talked in class, while others dozed off, oblivious to the teachers' lecture. I noticed one student, who was a heavy smoker, had cigarette burns on her arms and legs. She was obnoxious and frequently disrupted the teacher's lecture. There was no respect in the classroom. I didn't feel like I fit in. I was a dedicated and determined student. I was fired up and eager to learn. Their inattention during lectures and lack of motivation in school, on the other hand, struck me hard. I felt stupid and isolated. I was still unfamiliar with the term "learning disability," and these students made me think they were stupid. Furthermore, I felt like they reflected me, as if I were one of them, which I didn't like. The environment in which I was placed shaped my negative perceptions of learning disabilities in general.

Mathematics had never been my strong suit. In a resource class, I took basic math. It was the same basic mathematical problems I had learned the previous year.I had to repeat my basic math class because I didn't make enough progress, but I was allowed to complete the tasks at my own pace. I struggled with fractions, decimals, and percentages. I frequently forgot simple math facts. I had to use a calculator to calculate math problems over and over again until I got the numbers right and corrected the mistakes. When copying from the textbook and board, I was constantly making mistakes, and the numbers were frequently reversed. I had trouble organizing the mathematical problems and completing my assignments correctly. I had to use graph paper to keep columns aligned in written math assignments. It helped me organize the problems, but it did not always help me avoid making mistakes. I was unable to identify and correct simple math errors. It was extremely discouraging and frustrating.

I had a conflict with my teacher in my deaf program class. She would yell at me if I didn't understand a particular subject or made a mistake. She never told me, "Yes, you can do it," or encouraged me to do well. She crushed my spirit and convinced me that I would never succeed in life because of my academic difficulties. My classes were extremely difficult for me, so this was probably the most stressful and unhappy time of my life.

With my parents' support and encouragement, I was determined to fight against the odds in order to further my education. I gradually regained my confidence. Despite my academic difficulties, I aspired to be intelligent like Anne Shirley, the main character in the Anne of Green Gables series. Because this character loved books, she influenced me to appreciate books. Like Anne Shirley, I was determined to succeed in school and didn't want to give up (thanks, in part, to my Type A family). I was determined, out of anger, to prove that particular teacher and my friends wrong.

They did not adhere to classroom norms. During lectures, one of the students would usually get up and walk to the window to look out. Another student would lean back and gaze at the ceiling. Some of them talked in class, while others dozed off, oblivious to the teachers' lecture. I noticed one student, who was a heavy smoker, had cigarette burns on her arms and legs. She was obnoxious and frequently disrupted the teacher's lecture. There was no respect in the classroom. I didn't feel like I fit in. I was a dedicated and determined student. I was fired up and eager to learn. Their inattention during lectures and lack of motivation in school, on the other hand, struck me hard. I felt stupid and isolated. I was still unfamiliar with the term "learning disability," and these students made me think they were stupid. Furthermore, I felt like they reflected me, as if I were one of them, which I didn't like. The environment in which I was placed shaped my negative perceptions of learning disabilities in general.

Mathematics had never been my strong suit. In a resource class, I took basic math. It was the same basic mathematical problems I had learned the previous year.I had to repeat my basic math class because I didn't make enough progress, but I was allowed to complete the tasks at my own pace. I struggled with fractions, decimals, and percentages. I frequently forgot simple math facts. I had to use a calculator to calculate math problems over and over again until I got the numbers right and corrected the mistakes. When copying from the textbook and board, I was constantly making mistakes, and the numbers were frequently reversed. I had trouble organizing the mathematical problems and completing my assignments correctly. I had to use graph paper to keep columns aligned in written math assignments. It helped me organize the problems, but it did not always help me avoid making mistakes. I was unable to identify and correct simple math errors. It was extremely discouraging and frustrating.

I had a conflict with my teacher in my deaf program class. She would yell at me if I didn't understand a particular subject or made a mistake. She never told me, "Yes, you can do it," or encouraged me to do well. She crushed my spirit and convinced me that I would never succeed in life because of my academic difficulties. My classes were extremely difficult for me, so this was probably the most stressful and unhappy time of my life.

With my parents' support and encouragement, I was determined to fight against the odds in order to further my education. I gradually regained my confidence. Despite my academic difficulties, I aspired to be intelligent like Anne Shirley, the main character in the Anne of Green Gables series. Because this character loved books, she influenced me to appreciate books. Like Anne Shirley, I was determined to succeed in school and didn't want to give up (thanks, in part, to my Type A family). I was determined, out of anger, to prove that particular teacher and my friends wrong.

My Extreme Outburst

World history was the most difficult class I had at Annandale High School. It was not available in the resource class. To fulfill a school requirement, I had no choice but to enroll in this class with regular students without an interpreter. When I was frustrated with a subject, I would either yell or throw the book. My experience in world history class, on the other hand, was quite different. I was studying for the test with my mother's help one night. I couldn't understand the material, no matter how hard she tried to explain it to me.

I became so frustrated that I couldn't stand it any longer. I couldn't cling to the wall to relieve my frustration like I usually did. As a result, I blew up and ripped the book.My mother was sitting nearby, witnessing my outburst. I expected her to feel sorry for me or to console me, but she didn't. Instead, she gave me a stern look and said, "You need to learn how to control your frustration." She stormed out of the dining room, leaving me alone in the room where I usually studied. I was taken aback! I couldn't believe she'd toughened up. She was usually understanding of my frustration, but not this time.

I reflected on what my mother had just said. I realized that I usually clung to the wall to relieve my frustration. She was correct. It was time to knock down the wall and figure out how to deal with my frustration. In this case, I also have to thank my world history teacher for cheering me up when I saw her handwriting, "Follow your dreams," on my final exam (I received a C in this class). Thank goodness!).

Despite my efforts, I struggled in my classes. I did not have an interpreter in my classes at the time because I had not yet learned American Sign Language. My time at Annandale High School was miserable, and I have many bitter memories of it. Because of my bad experience at school, the wall had thickened again, making it more difficult to tear down.

I became so frustrated that I couldn't stand it any longer. I couldn't cling to the wall to relieve my frustration like I usually did. As a result, I blew up and ripped the book.My mother was sitting nearby, witnessing my outburst. I expected her to feel sorry for me or to console me, but she didn't. Instead, she gave me a stern look and said, "You need to learn how to control your frustration." She stormed out of the dining room, leaving me alone in the room where I usually studied. I was taken aback! I couldn't believe she'd toughened up. She was usually understanding of my frustration, but not this time.

I reflected on what my mother had just said. I realized that I usually clung to the wall to relieve my frustration. She was correct. It was time to knock down the wall and figure out how to deal with my frustration. In this case, I also have to thank my world history teacher for cheering me up when I saw her handwriting, "Follow your dreams," on my final exam (I received a C in this class). Thank goodness!).

Despite my efforts, I struggled in my classes. I did not have an interpreter in my classes at the time because I had not yet learned American Sign Language. My time at Annandale High School was miserable, and I have many bitter memories of it. Because of my bad experience at school, the wall had thickened again, making it more difficult to tear down.

My Nightmares Began

When my father was transferred to Travis AFB in California in 1990, I attended Vanden High School for my junior and senior years. To my dismay, I was initially placed in resource classes at Vanden High School. I didn't want to be a part of a learning disability program because I didn't think I had one. My placement in resource classes shattered my dreams and paved the way for nightmares. I was determined to transfer to regular classes in order to push myself and further my education.

The remedial English class was small, with only about five students with learning disabilities. I despised feeling stupid. I was adamant about getting out of this class. I eventually moved into some regular classes because I was learning faster than the other students. My classes finally had an interpreter. The wall was beginning to break down, but not completely. It was difficult, but I started to succeed because I had promised myself that I would do my best.

The remedial English class was small, with only about five students with learning disabilities. I despised feeling stupid. I was adamant about getting out of this class. I eventually moved into some regular classes because I was learning faster than the other students. My classes finally had an interpreter. The wall was beginning to break down, but not completely. It was difficult, but I started to succeed because I had promised myself that I would do my best.

Beating the Odds

I was driven to further my education and determined to beat the odds and start tearing down the wall. I was determined not to let the wall in front of me stop me from beating the odds. I would cling to the wall for comfort whenever I was frustrated. As much as I desired a good education, I had to work hard to break down the wall, despite the fact that it was extremely difficult to do so. With the wall being torn down piece by piece, I would be able to further my education and accelerate my academic progress without feeling frustrated.

Unfortunately, I never took biology during my four years of high school, and my foreign language requirement was waived. I did not take algebra or geometry in high school. I felt humiliated and ashamed of myself. I used to wrap a brown paper bag around my math and science books so no one would notice that I was only taking basic math and science.

I was embarrassed by my learning disability. Despite being crowned "Snowball Queen" and "Prom Queen" my senior year, I never told any of my high school friends about my learning disability. Because of my bad experience, I was sensitive to criticism from others, and I didn't want my friends to think I was stupid. Some of them were probably aware that I was placed in some of the resource classes, and they assumed it was primarily due to my deafness. I knew it had something to do with my learning disability.

Unfortunately, I never took biology during my four years of high school, and my foreign language requirement was waived. I did not take algebra or geometry in high school. I felt humiliated and ashamed of myself. I used to wrap a brown paper bag around my math and science books so no one would notice that I was only taking basic math and science.

I was embarrassed by my learning disability. Despite being crowned "Snowball Queen" and "Prom Queen" my senior year, I never told any of my high school friends about my learning disability. Because of my bad experience, I was sensitive to criticism from others, and I didn't want my friends to think I was stupid. Some of them were probably aware that I was placed in some of the resource classes, and they assumed it was primarily due to my deafness. I knew it had something to do with my learning disability.

Unprepared for College

After graduating from high school in 1992, I enrolled at Ohlone Community College in Fremont, California. When I took Algebra I for the first time, I was completely unprepared. When I couldn't understand the simplest algebraic expressions, the wall grew thicker. With my visual processing issues, seeing so many math problems on the textbook page became overwhelming. It was extremely difficult for me to visually organize mathematical problems, and I became easily confused if there were too many problems on the same page. The numbers and symbols appeared jumbled. It was difficult to sort through the clutter and visually differentiate between the math problems.

I couldn't use graph paper because it added to the clutter. Furthermore, the graph was too small to be used to organize the mathematical problems. I had to solve one problem to demonstrate my entire body of work. To solve the math problems, I had to separate the numbers and symbols and draw a line between them. The line helped me differentiate the numbers and symbols even though I was unaware of the color code system that I later learned from the tutoring services at Gallaudet University. It did, however, add a little more clutter than was necessary. It was a no-win situation at the time. See the following examples:

2x + 3y =

2x I + I 3y I =

I would spend hours at night completing assignments and studying for tests. When I couldn't understand the assignments, my Deaf friend, who was a math genius, would help me. I couldn't understand his explanation several times. When I couldn't understand his instruction and he showed his "shocked" expression, I felt degraded. (We dated for a short time. He eventually ended things with me because he thought I wasn't smart enough). It was extremely frustrating, and I frequently burst into tears. Despite my best efforts, I did not pass the class.

I didn't realize that college required much more reading and writing skills until I took my college-level English course after finishing my pre-college English courses. In high school, I never learned how to develop these skills. Due to my lack of exposure to early language and visual perception issues, I had difficulty expressing myself and organizing my work in writing. After weeks of struggle and with the assistance of a deaf friend who excelled in English, I began to understand the rules of the formal paper and quickly began to pick it up. Despite my best efforts, I only received a C. I was still in denial at the time; I didn't believe I had a learning disability. Because of my extreme frustration, the wall was re-emerging. I had to fight against erecting the wall in order to boost my motivation to learn while also learning how to deal with my frustration.

I couldn't use graph paper because it added to the clutter. Furthermore, the graph was too small to be used to organize the mathematical problems. I had to solve one problem to demonstrate my entire body of work. To solve the math problems, I had to separate the numbers and symbols and draw a line between them. The line helped me differentiate the numbers and symbols even though I was unaware of the color code system that I later learned from the tutoring services at Gallaudet University. It did, however, add a little more clutter than was necessary. It was a no-win situation at the time. See the following examples:

2x + 3y =

2x I + I 3y I =

I would spend hours at night completing assignments and studying for tests. When I couldn't understand the assignments, my Deaf friend, who was a math genius, would help me. I couldn't understand his explanation several times. When I couldn't understand his instruction and he showed his "shocked" expression, I felt degraded. (We dated for a short time. He eventually ended things with me because he thought I wasn't smart enough). It was extremely frustrating, and I frequently burst into tears. Despite my best efforts, I did not pass the class.

I didn't realize that college required much more reading and writing skills until I took my college-level English course after finishing my pre-college English courses. In high school, I never learned how to develop these skills. Due to my lack of exposure to early language and visual perception issues, I had difficulty expressing myself and organizing my work in writing. After weeks of struggle and with the assistance of a deaf friend who excelled in English, I began to understand the rules of the formal paper and quickly began to pick it up. Despite my best efforts, I only received a C. I was still in denial at the time; I didn't believe I had a learning disability. Because of my extreme frustration, the wall was re-emerging. I had to fight against erecting the wall in order to boost my motivation to learn while also learning how to deal with my frustration.

Facing Academic Hardship at Gallaudet University

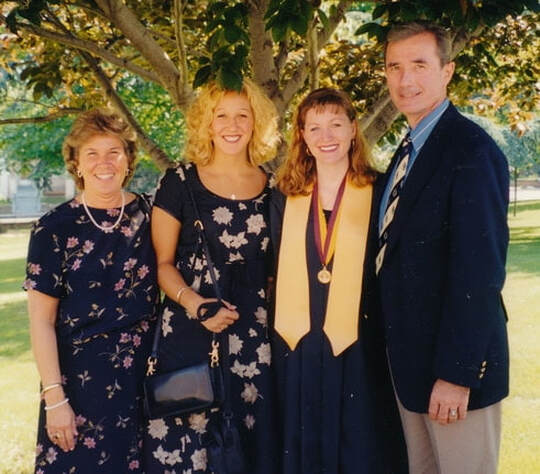

John, Jodi, Jeanne & Jami, 1997

John, Jodi, Jeanne & Jami, 1997

I transferred to Gallaudet University in 1994, at the age of twenty-one, where I faced increased academic challenges. My parents were stationed with the Air Force in Seoul, Korea, at the time, and I couldn't count on their help whenever I needed it. Years of academic difficulties enabled me to become a survivor and stronger person in the college environment. Our geographical separation also taught me to be independent and to develop my advocacy skills. Most importantly, facing academic challenges alone strengthened my determination to break down the wall. Nonetheless, I was still in denial.

Despite repeating my Algebra I course, I still struggled with math. It took me hours to complete my assignments and prepare for the tests. I was exhausted from studying for the tests, and I was frustrated by my inability to understand math. I was up against a brick wall. I received mostly Ds on the tests, no matter how hard I studied. The day before the final exam, we, the students, had to meet with our professor to receive our final grade. My final grade, a D plus, was exactly what I expected, but I was dissatisfied with my grade, especially since I still had to take the final exam. When my professor approached me and asked if she could look at my grade, I shed a tear. "Congratulations!" she said when I showed her my final classwork grade. "Now you must study hard for the final exam." "Thank you," I said, nodding. Why should I study hard when I received mostly Ds on my previous tests? That afternoon, I was determined to break through the wall by studying even harder, and I planned to celebrate even if I received a D in my math class. I enlisted the help of a math genius friend of mine. She agreed to help, so we sat down on the floor, and she began tutoring me in math. Her frustration grew as we went along because I couldn't understand her explanation. She couldn't take it any longer. She eventually ran out of patience. She slammed the book shut and threw it to the ground. "Why can't you understand math?" she asked. I burst out crying. "I don't know!" I exclaimed angrily. "Get out!" She quickly exited the room. I was crying alone in my dorm, and the exam was approaching. As soon as I calmed down, I debated whether I should study for the final exam or just forget about it. "Well, I'm not a quitter, and I'm not going to fail this course again," I reasoned. So I returned to my studies. I studied for the final exam for about twenty hours. I had only gotten one hour of sleep. I barely passed Algebra I after spending twenty hours studying for the final exam. It was a huge relief, but I knew it wasn't the end. The next course I had to take was Algebra II.

Equally, I struggled with English and enrolled in a non-credit English course to improve my reading and writing skills before advancing to the required English courses. My English teacher was skeptical that I would pass the English Placement Test because of my reading and writing difficulties, but he was wrong. I was successful. I also passed the Freshman Writing Exam in addition to the English Placement Test. As a result, my Ohlone College English course was transferred and waived. I began taking required English courses after passing the English Placement Test. While studying English, I gradually improved my reading comprehension and writing skills, though my progress was still slow and I needed time to process the information I read or wrote. I realized it was time to believe in myself and my ability to knock down the wall. Despite my academic challenges, I knew I could do it, though I was still skeptical of overcoming

My math struggle was about to resurface. Similarly to Algebra I, I studied Algebra II endlessly for the tests, and despite the assistance of a math tutor, who was a student, I did not do well. He tried his best to help, but his explanations did not correspond to my processing or learning style. He seemed surprised that I didn't understand his explanation during tutoring. I felt a little embarrassed. It had to be his first time tutoring a student like myself. Every time I got my math test results, I got an F. The wall around me grew even thicker, and I was unable to break it down. Despite my best efforts, I audited Algebra II because I was failing.

Similarly to my difficulties with math, I struggled to complete the language requirement for a Social Work degree. Academically, I couldn't handle Algebra II and a German class at the same time (I took German because I was born in Germany as an Air Force Brat and because my ancestors immigrated to America from Germany). I felt a connection to Germany, but I had no idea how difficult it was to learn a foreign language until I took it. When I compared myself to other students, I noticed that they picked up the language quickly. One student in particular had a photographic memory. For example, he spent 15 minutes studying for an exam, while I spent a week. I couldn't understand why I couldn't do the same. "This isn't a math class," I thought. "Why do I have to struggle in German too?" I was still in denial as the wall grew thicker. I knew I had to break down the wall, but I had no idea how to do so with this current academic requirement (later research revealed that those who struggle with math concepts also struggle with foreign languages).

Despite repeating my Algebra I course, I still struggled with math. It took me hours to complete my assignments and prepare for the tests. I was exhausted from studying for the tests, and I was frustrated by my inability to understand math. I was up against a brick wall. I received mostly Ds on the tests, no matter how hard I studied. The day before the final exam, we, the students, had to meet with our professor to receive our final grade. My final grade, a D plus, was exactly what I expected, but I was dissatisfied with my grade, especially since I still had to take the final exam. When my professor approached me and asked if she could look at my grade, I shed a tear. "Congratulations!" she said when I showed her my final classwork grade. "Now you must study hard for the final exam." "Thank you," I said, nodding. Why should I study hard when I received mostly Ds on my previous tests? That afternoon, I was determined to break through the wall by studying even harder, and I planned to celebrate even if I received a D in my math class. I enlisted the help of a math genius friend of mine. She agreed to help, so we sat down on the floor, and she began tutoring me in math. Her frustration grew as we went along because I couldn't understand her explanation. She couldn't take it any longer. She eventually ran out of patience. She slammed the book shut and threw it to the ground. "Why can't you understand math?" she asked. I burst out crying. "I don't know!" I exclaimed angrily. "Get out!" She quickly exited the room. I was crying alone in my dorm, and the exam was approaching. As soon as I calmed down, I debated whether I should study for the final exam or just forget about it. "Well, I'm not a quitter, and I'm not going to fail this course again," I reasoned. So I returned to my studies. I studied for the final exam for about twenty hours. I had only gotten one hour of sleep. I barely passed Algebra I after spending twenty hours studying for the final exam. It was a huge relief, but I knew it wasn't the end. The next course I had to take was Algebra II.

Equally, I struggled with English and enrolled in a non-credit English course to improve my reading and writing skills before advancing to the required English courses. My English teacher was skeptical that I would pass the English Placement Test because of my reading and writing difficulties, but he was wrong. I was successful. I also passed the Freshman Writing Exam in addition to the English Placement Test. As a result, my Ohlone College English course was transferred and waived. I began taking required English courses after passing the English Placement Test. While studying English, I gradually improved my reading comprehension and writing skills, though my progress was still slow and I needed time to process the information I read or wrote. I realized it was time to believe in myself and my ability to knock down the wall. Despite my academic challenges, I knew I could do it, though I was still skeptical of overcoming

My math struggle was about to resurface. Similarly to Algebra I, I studied Algebra II endlessly for the tests, and despite the assistance of a math tutor, who was a student, I did not do well. He tried his best to help, but his explanations did not correspond to my processing or learning style. He seemed surprised that I didn't understand his explanation during tutoring. I felt a little embarrassed. It had to be his first time tutoring a student like myself. Every time I got my math test results, I got an F. The wall around me grew even thicker, and I was unable to break it down. Despite my best efforts, I audited Algebra II because I was failing.

Similarly to my difficulties with math, I struggled to complete the language requirement for a Social Work degree. Academically, I couldn't handle Algebra II and a German class at the same time (I took German because I was born in Germany as an Air Force Brat and because my ancestors immigrated to America from Germany). I felt a connection to Germany, but I had no idea how difficult it was to learn a foreign language until I took it. When I compared myself to other students, I noticed that they picked up the language quickly. One student in particular had a photographic memory. For example, he spent 15 minutes studying for an exam, while I spent a week. I couldn't understand why I couldn't do the same. "This isn't a math class," I thought. "Why do I have to struggle in German too?" I was still in denial as the wall grew thicker. I knew I had to break down the wall, but I had no idea how to do so with this current academic requirement (later research revealed that those who struggle with math concepts also struggle with foreign languages).

Another Official Diagnosis

I was filled with anger and despair. While reflecting on my academic struggles since childhood, I realized I might have a learning disability. I chose to be re-evaluated to confirm the initial testing results. The students were required by Gallaudet University policy to complete their math courses within two years. I was afraid that if I kept putting it off or failed Algebra II, I would not be able to finish my degree.

In the spring of 1995, I met with Dr. Anthony B. Wolff, a psychologist who knew sign language, after requesting a referral from the Gallaudet's Office for Students with Disabilities. The evaluation report arrived three weeks later, and it was time to learn the results. When I read the evaluation report, I was astounded to discover that the results of the second evaluation were similar to those of Annandale High School. My mother informed me via e-mail that the evaluation report showed identical results to those I had in high school. It was true. I thought, "Well, my high school psychologist was right, after all." Needless to say, I did not regret repeating the evaluation. I just wanted to know what the results meant for my life and my learning challenges.

The evaluation revealed that I had a learning disability, which included a visual-spatial disorder and a slow processing speed. This time, I accepted the fact that I had learning disabilities. Because it clarified my frustration, showed me where my areas of strength and weakness lay, and provided me with a strategy for focusing on and enhancing my academic abilities, it marked the beginning of my self-awareness. The evaluation acted as a road map. It helped me figure out how to navigate college to do well academically. I had to put a lot of effort into improving my learning, and I never gave up on breaking down the wall while it was still standing.

In the spring of 1995, I met with Dr. Anthony B. Wolff, a psychologist who knew sign language, after requesting a referral from the Gallaudet's Office for Students with Disabilities. The evaluation report arrived three weeks later, and it was time to learn the results. When I read the evaluation report, I was astounded to discover that the results of the second evaluation were similar to those of Annandale High School. My mother informed me via e-mail that the evaluation report showed identical results to those I had in high school. It was true. I thought, "Well, my high school psychologist was right, after all." Needless to say, I did not regret repeating the evaluation. I just wanted to know what the results meant for my life and my learning challenges.

The evaluation revealed that I had a learning disability, which included a visual-spatial disorder and a slow processing speed. This time, I accepted the fact that I had learning disabilities. Because it clarified my frustration, showed me where my areas of strength and weakness lay, and provided me with a strategy for focusing on and enhancing my academic abilities, it marked the beginning of my self-awareness. The evaluation acted as a road map. It helped me figure out how to navigate college to do well academically. I had to put a lot of effort into improving my learning, and I never gave up on breaking down the wall while it was still standing.

Developing Coping Strategies

Regardless of my diagnosis of visual-spatial processing challenges, I was determined to succeed in college. Therefore, I requested accessibility accommodations from the Office for Students with Disabilities. A psychologist advised taking tests orally and for an extended period of time. Nonetheless, I completed the classroom tests and was always the last to finish them. If I couldn't finish the tests in the allotted time, I would have used the testing accommodations.

In terms of academic challenges, I had to learn to compensate for my learning disabilities and use alternative learning methods. Nobody had ever taught me how to create a coping strategy. It was primarily self-taught. I learned to develop and implement compensatory strategies based on my present strengths and skills. For example, due to my issues with visual perception, I often needed to remember the basic facts after reading them silently. Because I couldn't access the information through the auditory channel, I had to use my tactile/kinesthetic skills to write down facts so I wouldn't forget them. In addition, when reading textbooks, I would summarize the information on notes, which I would then use to study for the test. Finally, I had to trace the letters, numbers, and words I was trying to remember. The procedure was time-consuming but effective and beneficial.

The only way to break through the wall was to relearn my study skills and coping strategies because what worked for me in high school was insufficient for the demands of college. As my classes became more difficult, I learned to improve my study skills and coping strategies, such as writing and test-taking strategies, time-management strategies, and organizational strategies for researching articles. These strategies helped me keep my head above water. While studies had taken over my life, I was also probably overly organized. I had to keep everything in order, including my pre-planning during the holidays and summer break. To-do lists were constantly ruling my life. A well-organized structure reinforced my ability to navigate college. My learning disabilities remained a barrier to my academic success, but I was determined to overcome them by using my study skills and coping strategies to further my education.

In terms of academic challenges, I had to learn to compensate for my learning disabilities and use alternative learning methods. Nobody had ever taught me how to create a coping strategy. It was primarily self-taught. I learned to develop and implement compensatory strategies based on my present strengths and skills. For example, due to my issues with visual perception, I often needed to remember the basic facts after reading them silently. Because I couldn't access the information through the auditory channel, I had to use my tactile/kinesthetic skills to write down facts so I wouldn't forget them. In addition, when reading textbooks, I would summarize the information on notes, which I would then use to study for the test. Finally, I had to trace the letters, numbers, and words I was trying to remember. The procedure was time-consuming but effective and beneficial.

The only way to break through the wall was to relearn my study skills and coping strategies because what worked for me in high school was insufficient for the demands of college. As my classes became more difficult, I learned to improve my study skills and coping strategies, such as writing and test-taking strategies, time-management strategies, and organizational strategies for researching articles. These strategies helped me keep my head above water. While studies had taken over my life, I was also probably overly organized. I had to keep everything in order, including my pre-planning during the holidays and summer break. To-do lists were constantly ruling my life. A well-organized structure reinforced my ability to navigate college. My learning disabilities remained a barrier to my academic success, but I was determined to overcome them by using my study skills and coping strategies to further my education.

Slow Processing Speed

Before starting college in the fall of 1995, I knew I had to overcome my apprehension about taking the general education requirements. To deal with my frustration in certain classes, I devised coping strategies. As I reviewed the curriculum, my first thought was to cope by balancing light and heavy course loads semester by semester. During summer school, I would also take difficult or uninteresting courses. Following that, I took two courses per summer semester (one course per three-week session) to graduate on time.

There was one summer course in particular that I will never forget. It was biology, and I had never taken science in high school. Kim, my roommate, and I took this class together. When I saw her quick study pace, I was astounded at how slow my processing was. Kim and I would study together the night before the test, say at 6:00 p.m. She had finished the book and was getting ready for bed by 11:00 p.m. I asked her if she was finished with her studies. "Yes," she replied. "How about you?" "No, I need to study more," I replied. "OK, good night," she said, nodding. I turned to look at the book as she jumped into bed. I was taken aback. I couldn't believe it. Although I was aware of my reading and processing speed limitations, I had no idea how bad my processing speed was until that night. She had finished all four chapters in four hours. I was still in chapter two, with two chapters left! It was getting late. Despite the circumstances, I continued to study until 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. Kim and I got up at 6:00 a.m. to review our notes for the test. As a result, we both received the same grade—a B! Whether I liked it or not, I had to study for longer hours than my peers.

There was one summer course in particular that I will never forget. It was biology, and I had never taken science in high school. Kim, my roommate, and I took this class together. When I saw her quick study pace, I was astounded at how slow my processing was. Kim and I would study together the night before the test, say at 6:00 p.m. She had finished the book and was getting ready for bed by 11:00 p.m. I asked her if she was finished with her studies. "Yes," she replied. "How about you?" "No, I need to study more," I replied. "OK, good night," she said, nodding. I turned to look at the book as she jumped into bed. I was taken aback. I couldn't believe it. Although I was aware of my reading and processing speed limitations, I had no idea how bad my processing speed was until that night. She had finished all four chapters in four hours. I was still in chapter two, with two chapters left! It was getting late. Despite the circumstances, I continued to study until 2:00 or 3:00 a.m. Kim and I got up at 6:00 a.m. to review our notes for the test. As a result, we both received the same grade—a B! Whether I liked it or not, I had to study for longer hours than my peers.

Using the Color Code System

Jodi & Linda Williams

Jodi & Linda Williams

A trial Algebra II class was created in collaboration with Dr. Stephen F. Weiner, Dean of Student Affairs and Academic Support, the Office for Students with Disabilities, and the Mathematics Department. This one-year course was designed for students with learning disabilities. I enrolled in this class, and the pace of instruction was slower. Linda Williams, a full-time tutor specialist, was also assigned to me. She used the color-code system as one of her techniques. As I went through the steps, she used it to organize the complex math problems. I was amazed for the first time in years to finally be able to decipher the numbers and symbols. I didn't have to separate the numbers and symbols by drawing lines between them. See the following example:

2x + 3y=

Color coding helped me pass this course with a C. One day in the hall, I ran into Jean Schickel, my math professor. She mentioned that this class was no longer offered and that many students struggled with math in their regular classes. The Math Department had decided to discontinue teaching this course for whatever reason. Like other postsecondary institutions, Gallaudet University eventually offered qualified students a substitution for a math course. This option, however, was not available to me until I enrolled in Gallaudet's graduate program. To summarize, Ms. Schickel stated that I was extremely fortunate to have taken this class at the time that I did because I would not have been able to graduate otherwise. Fast forward to 2022, when my daughter, who is enrolled at Gallaudet University, discovered, to our surprise, that, unlike many other postsecondary institutions, they do not offer math course substitutions.

As a social work major, I was required to take a statistics course. It was something I couldn't get away from. I understood the concepts during the lecture, but I couldn't complete the work correctly. In order for me to pass this course, the Social Work Department assigned a Gallaudet professor, Robert B. Weinstock, to tutor me weekly. I did poorly on the statistics tests, as expected. I passed the class thanks to the strength of my research papers

2x + 3y=

Color coding helped me pass this course with a C. One day in the hall, I ran into Jean Schickel, my math professor. She mentioned that this class was no longer offered and that many students struggled with math in their regular classes. The Math Department had decided to discontinue teaching this course for whatever reason. Like other postsecondary institutions, Gallaudet University eventually offered qualified students a substitution for a math course. This option, however, was not available to me until I enrolled in Gallaudet's graduate program. To summarize, Ms. Schickel stated that I was extremely fortunate to have taken this class at the time that I did because I would not have been able to graduate otherwise. Fast forward to 2022, when my daughter, who is enrolled at Gallaudet University, discovered, to our surprise, that, unlike many other postsecondary institutions, they do not offer math course substitutions.

As a social work major, I was required to take a statistics course. It was something I couldn't get away from. I understood the concepts during the lecture, but I couldn't complete the work correctly. In order for me to pass this course, the Social Work Department assigned a Gallaudet professor, Robert B. Weinstock, to tutor me weekly. I did poorly on the statistics tests, as expected. I passed the class thanks to the strength of my research papers

Receiving a Social Work Professional Development Award

Jodi Becker & Charlotte Kaldani, 1998

Jodi Becker & Charlotte Kaldani, 1998

During my senior year at Gallaudet University, I received a Social Work Professional Development Award. The Social Work Department was impressed with my ability to plan ahead for writing assignments and to ask my professors for clarification prior to the actual due dates. Unlike most of my friends, I had to write a paper little by little in advance, or I would get a mental block and be paralyzed by the thought of having to write a paper at the last minute. Having said that, I wrote better when I was not under stress or pressure (the Social Work Department required a lot of term papers). Charlotte Kaldani Simoes, my Gallaudet roommate and an accounting major, usually chuckled when I brought library books to our dorm immediately after the assignment due date was announced and began working on the paper. I was fortunate to have her as a roommate because she was equally dedicated to her studies. We had an excellent study system. Even though the wall was still standing, I planned ahead of time for paper due dates, exams, and assignment deadlines throughout my college career because I was afraid of failing.

Graduating Cum Laude

Throughout the last four years, I have done well in the majority of my classes. At graduation rehearsal, it was announced that I had made the Cum Laude list. What?! I never imagined this would happen in a million years! Despite having previously made the Dean's List, I did not expect to receive the highest grade. I worked only to the best of my ability. I thought it was a mistake to graduate Cum Laude and sought confirmation from the academic advisor who made the announcement. "No, it's not a mistake," she said as she pointed to my name on the list. In 1998, I received my Bachelor of Science Degree in Social Work from Gallaudet University. After six years of study, it felt great to finally graduate. On the other hand, I didn't feel like the wall was completely gone, and the battle was far from over.

Nose Buried in Books and Writing Papers

Duane & Jodi, 1998

Duane & Jodi, 1998

Shortly after graduating from Gallaudet University, I enrolled in Gallaudet's Graduate School of Social Work to further my education and prepare for the job market. At the time, most counseling jobs required a master's degree. Before I started the program, it was suggested that I enroll in the four-year program rather than the two-year program because I might not be able to handle the heavy workload, which included many term papers. However, financial aid would not cover a part-time student, and I wanted to finish my degree in two years. I decided to challenge myself to do my best and enrolled in a two-year program in addition to internships, which were granted. I spent countless hours in graduate school with my nose buried in books and writing papers. In comparison to undergraduate school, I had very little social life. I was overworked. I was barely able to keep my head above water. As a newlywed, my husband, Duane, who recently graduated from Gallaudet, took care of cooking, cleaning, laundry, and other household chores so that I could concentrate on my studies. I couldn't focus on anything else. I honestly could not have survived without him.

To better understand learning disabilities in general, I enrolled in an American University course taught by professor Sally L. Smith, the founder of the Lab School of Washington for students with learning disabilities and a national leader in the field of learning disabilities. I realized why I was always tired for the first time in years. For a long time, I assumed something was wrong with my health, such as low iron. Despite numerous doctor visits, I was declared completely healthy. My mother suspected it was due to my mental exertion, which caused fatigue or exhaustion. I didn't believe it was the case. I eventually came across Sally's book, which stated that students with learning disabilities are likely tired due to the mental work required to decipher the visual material. Sally's book confirmed it, but I had never thought of that connection! After all, my mother was correct.

During my first year of graduate school, I was still up against a brick wall. I passed the qualification examination at the end of the year, but I failed a required Audiology class with a C+ (I needed a B or higher) and had to repeat it. I was devastated and thought it was the end of the world!

To better understand learning disabilities in general, I enrolled in an American University course taught by professor Sally L. Smith, the founder of the Lab School of Washington for students with learning disabilities and a national leader in the field of learning disabilities. I realized why I was always tired for the first time in years. For a long time, I assumed something was wrong with my health, such as low iron. Despite numerous doctor visits, I was declared completely healthy. My mother suspected it was due to my mental exertion, which caused fatigue or exhaustion. I didn't believe it was the case. I eventually came across Sally's book, which stated that students with learning disabilities are likely tired due to the mental work required to decipher the visual material. Sally's book confirmed it, but I had never thought of that connection! After all, my mother was correct.

During my first year of graduate school, I was still up against a brick wall. I passed the qualification examination at the end of the year, but I failed a required Audiology class with a C+ (I needed a B or higher) and had to repeat it. I was devastated and thought it was the end of the world!

Knocking Down the Wall

I took more courses during my second year of graduate school in order to graduate on time. I wasn't sure if I could do it because I had only taken four courses per semester during my first three years of social work programs (two years as an undergraduate and one year as a graduate student), and it fit my limitations. I was afraid to continue my education for fear of failing again. I couldn't bear the thought of failing, especially since I was so close to finishing my degree. I wasn't quite ready to give up.

I was overjoyed to finally understand the material completely as I finished my second year of graduate school. Despite my slow processing speed, my learning and thinking processes became clearer than ever. As a result of my diligent summer reading, my reading and writing skills have greatly improved! My classes were all passed, including the one I had to retake. I believe that not having to take math or statistics during my second year of graduate school helped me. Despite my long academic struggle, it turned out that I had finally broken through the wall. The wall is no longer there! I'm having fun learning for the first time in a long time! For eight years of college work, I gradually chipped away at the wall before finally knocking it down!

I finished my master's degree in social work in May 2000. My English term paper, ironically titled, "How did college students with learning disabilities overcome academic work obstacles, and what kind of services and programs should colleges and universities provide?" inspired me to major in social work and work as an accessibility advisor at Salt Lake Community College's Disability Resource College. Furthermore, I would not be who I am today if it weren't for the Anne of Green Gables books/videos (I had the opportunity to read the entire series during my first year at Gallaudet).

Accepting my learning disability and fighting the wall I built around myself was a long and difficult journey. I have not outgrown my visual and slow processing issues. Despite years of living with the wall, it took a while to process information and learn how to compensate for my learning challenges.