Difficulty Identifying a Learning Disability

in the Deaf & Hard of Hearing Population

The term “learning disabilities” was coined by Dr. Sam Kirk in 1963. There are different types of learning disabilities, and they are:

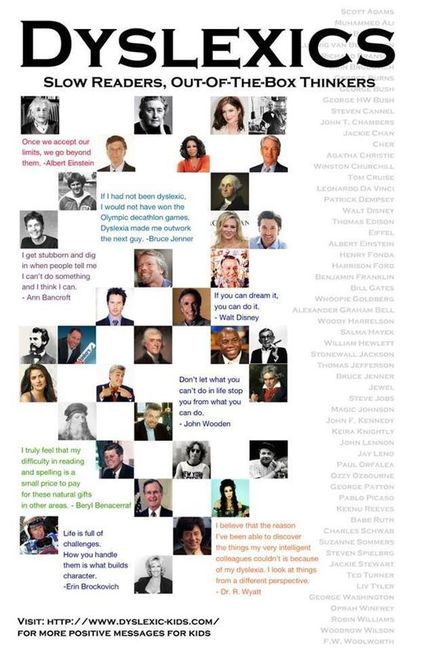

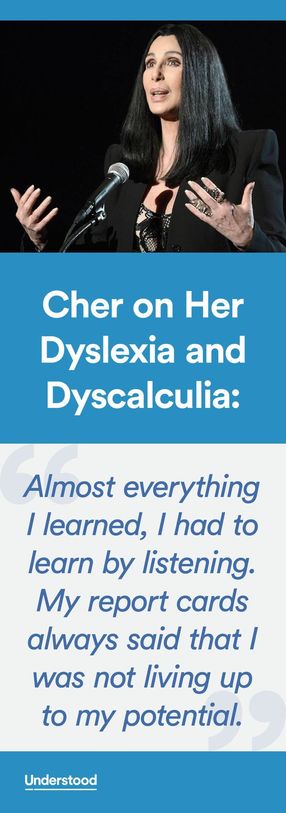

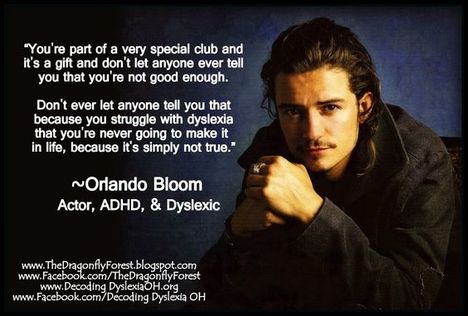

- Dyslexia – difficulties with specific language skills, mainly reading

- Dyscalculia – challenges in processing math

- Dysgraphia – difficulties with spelling, poor handwriting, and trouble putting thoughts on paper

- Auditory Processing Disorder – difficulties recognizing and interpreting information by sound

- Visual Processing Disorder – difficulties recognizing and interpreting information by sight

A learning disability is a neurological disorder. It denotes that a person's brain functions or is structured differently. Processing issues affect one's ability to read, write, spell, reason, organize information, and perform mathematics. Some students have one or two types of learning disabilities that affect various modes of learning. A student with dyslexia, for example, struggles with reading, writing, and spelling but excels in math and science. In the case of a student with dyscalculia, the student struggles with math but excels in English. Some students have both dyslexia and dyscalculia. A visual processing disorder can affect some or all aspects of academic learning, including reading, writing, spelling, and math.

Educators who work with deaf and hard of hearing students have long expressed concern that their students do not process academically as well as others. Furthermore, many students were unable to keep up with their peers. They struggle to understand language and mathematical concepts, making it difficult for them to succeed in school.

There are several reasons why identifying deaf and hard of hearing students with suspected learning disabilities is difficult. One of the elements is that there is some disagreement about how the term "learning disabled hearing impaired" should be defined. Deaf and hard of hearing children are not permitted to be classified as learning disabled because Public 94-142 states that children with learning disabilities cannot be classified as learning disabled if their difficulties are caused by a sensory deficit (Plapinger & Sokora, 1990). Another factor is that it is difficult to determine whether their language challenges are caused by a hearing loss or a learning disability (Plapinger & Sokora, 1990). With these issues, it is important to implement criteria for comparing the characteristics of deaf and hard of hearing students that differentiate them from non-learning disabled deaf and hard of hearing students (Plapinger & Sokora, 1990).

Due to language and reading delays, some deaf and hard of hearing students are overdiagnosed with a learning disability. According to LaSasso (1985, 1992), their language and reading delays are frequently misinterpreted as a learning disability when they are actually the norm for deaf or hard of hearing individuals. It can be difficult to determine whether or not deaf or hard of hearing students have a learning disability due to academic delays, particularly language delays caused by hearing loss, due to various types of processing problems. Psychologists also misdiagnose deaf and hard of hearing people for learning disabilities due to a lack of understanding of deafness and the interpretation of test results. They are also unable to communicate with them due to a lack of sign language skills. The assessment should include teacher observations, appropriate standardized assessment measures, and informal assessment procedures to determine the type of processing problems they have.

Unfortunately, there is a scarcity of test instruments and qualified evaluators to meet the needs of deaf and hard of hearing students suspected of having a learning disability. There aren't many standard test instruments for them, and there aren't many appropriate psychological and educational tests for assessing processing issues. When deaf and hard of hearing students struggle with reading and other subjects, it is critical to determine whether they have learning disabilities or if their difficulties are due to hearing loss (Plapinger & Sikora, 1990).

With the right training, teachers can identify their students' processing issues and refer them to a psychologist for an evaluation. It is recommended that a psychologist include the DSM-5 Set of Diagnostic Criteria on the student's evaluation report. It will inform the student and family of their current situation and address the student's specific learning needs in positive and effective ways, allowing him or her to learn more easily. For example, my fourth-grade daughter was tested for a possible learning disability at her previous school. Her psychological evaluation revealed that she had visual-spatial processing issues as well as functional limitations. She didn't understand why she was struggling academically because she was so young. Despite our help, she was lost and without guidance. As a result, her academic difficulties persisted, as did her frustration. In high school, she was retested for confirmation (at a different deaf school) and received the same diagnosis results.She was finally old enough to comprehend her diagnosis and functional limitations. To my surprise, she began to make academic progress and develop coping strategies to compensate for her learning challenges. As I mentioned in my "Tearing Down the Wall" story, my diagnosis clarified my frustration, revealed my areas of strength and weakness, and provided me with a strategy for focusing on and improving my academic abilities; it was the beginning of my self-awareness. The evaluation served as a guideline. It assisted me in figuring out how to navigate college in order to succeed academically. As a result, I cannot emphasize enough how critical it is for the psychologist to include the diagnosis in their report in order to provide better guidance, as described above.

Did You Know?

My daughter DJK is an inspiration to me because she had the guts to tell her friend that she has learning disabilities. An academically gifted friend told DJK in the fall of 2018 that she thought people with learning disabilities were stupid. DJK told her that she has LD as an act of defense. "It's impossible!" "You look smart," exclaimed her friend, who was in disbelief. DJK also revealed to her that one of their friends has an LD (in reading comprehension). She was at a loss for words. Through the conversation, the other friend—who is also academically gifted—shared that her brother—who is also deaf—has a learning disability in math. She was astounded. That cracked me up. I am incredibly proud of DJK for speaking up. To understand and empathetically assist academically challenged students, Deaf Education may require training in language deprivation, learning disabilities, and Irlen Syndrome. (They all come from Deaf families and attend the same deaf school.)

My daughter DJK is an inspiration to me because she had the guts to tell her friend that she has learning disabilities. An academically gifted friend told DJK in the fall of 2018 that she thought people with learning disabilities were stupid. DJK told her that she has LD as an act of defense. "It's impossible!" "You look smart," exclaimed her friend, who was in disbelief. DJK also revealed to her that one of their friends has an LD (in reading comprehension). She was at a loss for words. Through the conversation, the other friend—who is also academically gifted—shared that her brother—who is also deaf—has a learning disability in math. She was astounded. That cracked me up. I am incredibly proud of DJK for speaking up. To understand and empathetically assist academically challenged students, Deaf Education may require training in language deprivation, learning disabilities, and Irlen Syndrome. (They all come from Deaf families and attend the same deaf school.)

Difficulty Diagnosing a Learning Disability

in Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students

Diagnosing a learning disability in a deaf or hard of hearing student is difficult due to a lack of assessment instruments and qualified evaluators who meet with deaf and hard of hearing students who have suspected learning disabilities. There are few standard test instruments for these students, and even fewer appropriate psychological and educational tests for assessing their learning process (Rush & Baechle, 1992). These factors contribute to deaf and hard of hearing students' inability to receive appropriate services in the secondary and postsecondary system.

Because of their lack of understanding of deafness and the interpretation of test results, evaluators misdiagnose deaf and hard of hearing people for learning disabilities. They are unable to communicate with students due to the evaluators' lack of sign language skills. It is critical that the evaluator and student communicate directly. Nonetheless, if the evaluator doesn't know sign language, a certified interpreter must be provided so that they can communicate clearly with a deaf or hard of hearing student and keep the scores from being affected.

Due to their reading and writing delays, evaluators frequently misdiagnose deaf and hard of hearing individuals for having learning disabilities. It is not always the case that deaf and hard of hearing students' literacy skills are delayed. According to LaSasso (1985, 1992), their language and reading delays are frequently misinterpreted as a learning disability when, in fact, they are the norm for deaf or hard of hearing people.

LaSasso (1985, 1992) acknowledges that language and reading delays are often mistaken for a learning disability when they are actually the norm for deaf or hard of hearing people. For example, a 9-year-old deaf child is at the first-grade level, which is normal. By the time the child is 15, they should be reading at a third or fourth grade level. If the same child was still reading at the first-grade level at age 15, it would be very likely that they had learning disabilities (Morgan & Vernon, 1994). This is an example of how to spot learning disabilities in deaf and hard of hearing students. It doesn't mean it's okay for them to stay at their reading level because they have hearing loss and/or a learning disability. It's somewhat unacceptable to me. We have tools and strategies to assist students with reading, as mentioned in the "Resources/Services" section. In this case, with positive encouragement and push, they CAN improve their reading skills. The tools can also assist in the development of their improved reading skills.

Deaf and hard of hearing students face learning to read and write challenges. Reading and writing are difficult for them to learn for two reasons. First, when they start school, most do not have the same language skills as their hearing peers. As a result, they develop their language skills when they begin learning to read. They also struggle to follow language rules. Second, auditory measures are used to build reading skills. Decoding is complex because they do not provide auditory feedback (Plapinger & Sikora, 1990). When deaf and hard of hearing students struggle with reading and other subjects, it is critical to determine whether they have learning disabilities or if their learning disabilities result from their hearing loss (Plapinger & Sikora, 1990). As a result, guidelines need to be established for these students with learning disabilities to be correctly diagnosed. To assess deaf and hard of hearing students for learning disabilities, evaluators must be well-versed in the following:

Before providing an assessment, evaluators should always consider the students' educational background, cultural background, academic records, primary language, family and medical histories, and audiogram. Data collection is essential because evaluators need to know where a student is coming from. Most importantly, the data can help them be cautious when diagnosing a student with suspected learning disabilities. After gathering data, they should determine their academic strengths and weaknesses to compensate for academic obstacles and receive reasonable accommodations. The evaluation should also include verbal and nonverbal reasoning, language processing, memory, visual-motor skills, executive functioning and attention, and reading, writing, and/or mathematics achievement. They can then understand and work on the student's strengths and weaknesses by evaluating various aspects.

As I mentioned in my "Tearing Down the Wall" story, if you are deaf or hard of hearing and suspect you have a learning disability, make sure to choose an evaluator who is aware of deaf issues and knows sign language for the diagnosis. My high school psychologist was unusual; it doesn't happen all that often. If you can't find one, a certified interpreter should be provided. Keep in mind that evaluators must avoid misdiagnosing deaf and hard of hearing people with learning disabilities. Deaf and hard of hearing people are increasingly being identified as having a learning disability. It is critical that they receive appropriate services in order to progress and advance in their education by making reasonable accommodations.

Evaluators must be aware of the assessment instruments that must be used to assess deaf and hard of hearing students for a possible learning disability.

For more information on how to assess students for a possible learning disability, please see the enclosed link to the "Guidelines for Documentation of a Learning Disability in Gallaudet University Student."

Because of their lack of understanding of deafness and the interpretation of test results, evaluators misdiagnose deaf and hard of hearing people for learning disabilities. They are unable to communicate with students due to the evaluators' lack of sign language skills. It is critical that the evaluator and student communicate directly. Nonetheless, if the evaluator doesn't know sign language, a certified interpreter must be provided so that they can communicate clearly with a deaf or hard of hearing student and keep the scores from being affected.

Due to their reading and writing delays, evaluators frequently misdiagnose deaf and hard of hearing individuals for having learning disabilities. It is not always the case that deaf and hard of hearing students' literacy skills are delayed. According to LaSasso (1985, 1992), their language and reading delays are frequently misinterpreted as a learning disability when, in fact, they are the norm for deaf or hard of hearing people.

LaSasso (1985, 1992) acknowledges that language and reading delays are often mistaken for a learning disability when they are actually the norm for deaf or hard of hearing people. For example, a 9-year-old deaf child is at the first-grade level, which is normal. By the time the child is 15, they should be reading at a third or fourth grade level. If the same child was still reading at the first-grade level at age 15, it would be very likely that they had learning disabilities (Morgan & Vernon, 1994). This is an example of how to spot learning disabilities in deaf and hard of hearing students. It doesn't mean it's okay for them to stay at their reading level because they have hearing loss and/or a learning disability. It's somewhat unacceptable to me. We have tools and strategies to assist students with reading, as mentioned in the "Resources/Services" section. In this case, with positive encouragement and push, they CAN improve their reading skills. The tools can also assist in the development of their improved reading skills.

Deaf and hard of hearing students face learning to read and write challenges. Reading and writing are difficult for them to learn for two reasons. First, when they start school, most do not have the same language skills as their hearing peers. As a result, they develop their language skills when they begin learning to read. They also struggle to follow language rules. Second, auditory measures are used to build reading skills. Decoding is complex because they do not provide auditory feedback (Plapinger & Sikora, 1990). When deaf and hard of hearing students struggle with reading and other subjects, it is critical to determine whether they have learning disabilities or if their learning disabilities result from their hearing loss (Plapinger & Sikora, 1990). As a result, guidelines need to be established for these students with learning disabilities to be correctly diagnosed. To assess deaf and hard of hearing students for learning disabilities, evaluators must be well-versed in the following:

- Deaf and hard of hearing students’ communication modes.

- Deaf students’ unique culture known as Deaf Culture.

- How degree of hearing loss and types of educational experiences affect these students.

- These students’ functions in the areas of cognition, intelligence, academic achievement, and social-emotional functioning.

- The appropriate assessment technique of deaf and hard of hearing students.

- The discrepancies between potential and achievement among these students (Kachman, 1999, Morgan & Vernon, 1994).

Before providing an assessment, evaluators should always consider the students' educational background, cultural background, academic records, primary language, family and medical histories, and audiogram. Data collection is essential because evaluators need to know where a student is coming from. Most importantly, the data can help them be cautious when diagnosing a student with suspected learning disabilities. After gathering data, they should determine their academic strengths and weaknesses to compensate for academic obstacles and receive reasonable accommodations. The evaluation should also include verbal and nonverbal reasoning, language processing, memory, visual-motor skills, executive functioning and attention, and reading, writing, and/or mathematics achievement. They can then understand and work on the student's strengths and weaknesses by evaluating various aspects.

As I mentioned in my "Tearing Down the Wall" story, if you are deaf or hard of hearing and suspect you have a learning disability, make sure to choose an evaluator who is aware of deaf issues and knows sign language for the diagnosis. My high school psychologist was unusual; it doesn't happen all that often. If you can't find one, a certified interpreter should be provided. Keep in mind that evaluators must avoid misdiagnosing deaf and hard of hearing people with learning disabilities. Deaf and hard of hearing people are increasingly being identified as having a learning disability. It is critical that they receive appropriate services in order to progress and advance in their education by making reasonable accommodations.

Evaluators must be aware of the assessment instruments that must be used to assess deaf and hard of hearing students for a possible learning disability.

For more information on how to assess students for a possible learning disability, please see the enclosed link to the "Guidelines for Documentation of a Learning Disability in Gallaudet University Student."

Can a Deaf and Hard of Hearing Student

Have a Learning Disability

Under the Special Education Guidelines?

Researchers and practitioners are caught in a bind due to gaps in the definition of the "learning disabled hearing impaired." According to Public Law 94-142, there are two reasons why the definition of learning disabilities is inappropriate for deaf and hard of hearing students. The first reason is that deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals cannot be classified as learning disabled due to hearing loss. This law does not apply to people who have problems primarily due to visual, hearing, or other sensory impairments. As a result, they are not eligible to be classified as having learning disabilities. The second reason is to determine whether the language deficits are caused by deafness or a learning disability. Despite the shortcomings of the "legal" definition of learning disabilities, qualified professionals could classify deaf and hard of hearing students as learning disabled.

Educators question whether deaf and hard of hearing students are eligible to be classified as learning disabled and receive special education services based on this condition (Bunch & Melnky, 1989; LaSasso, 1985). As a result, the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (NJCLD) revised the definition to remove the federal barrier to developing services for deaf and hard of hearing students with learning disabilities in the school system. "Learning disabilities" are defined by the NJCLD as "conditions or influences that occur concurrently with other handicaps (for example, sensory impairment, mental retardation, or serious emotional disturbance) or extrinsic influences (such as cultural difference, insufficient, or inappropriate instruction), but are not the result of these conditions or influences" (Bunch & Melynk, 1989, p. 298).

Educators question whether deaf and hard of hearing students are eligible to be classified as learning disabled and receive special education services based on this condition (Bunch & Melnky, 1989; LaSasso, 1985). As a result, the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (NJCLD) revised the definition to remove the federal barrier to developing services for deaf and hard of hearing students with learning disabilities in the school system. "Learning disabilities" are defined by the NJCLD as "conditions or influences that occur concurrently with other handicaps (for example, sensory impairment, mental retardation, or serious emotional disturbance) or extrinsic influences (such as cultural difference, insufficient, or inappropriate instruction), but are not the result of these conditions or influences" (Bunch & Melynk, 1989, p. 298).

The federal definition states that "there are no... hearing impaired learning disabled children in the world—the idiocy of such a rule denies the evidence" (Sabatino, 1983, p. 26). The definition of learning disabilities was also criticized by Hammill, Leigh, McNutt, and Larsen (1981). They conclude that it is a misconception that learning disabilities cannot occur in the presence of other handicapping conditions or environmental, cultural, or economic advantages.

I beg to differ, as I mentioned in my "Tearing Down the Wall" story. Regardless of the issue with the "legal" definition of learning disabilities, qualified professionals should classify deaf and hard-of-hearing students as learning disabled if they have identified learning disabilities. I am convinced that there are deaf and hard of hearing students with learning disabilities. They are entitled to be classified as having learning disabilities and to receive appropriate services from secondary and postsecondary institutions. After all, I am living proof of the situation.

Educators question whether deaf and hard of hearing students are eligible to be classified as learning disabled and receive special education services based on this condition (Bunch & Melnky, 1989; LaSasso, 1985). As a result, the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (NJCLD) revised the definition to remove the federal barrier to developing services for deaf and hard of hearing students with learning disabilities in the school system. "Learning disabilities" are defined by the NJCLD as "conditions or influences that occur concurrently with other handicaps (for example, sensory impairment, mental retardation, or serious emotional disturbance) or extrinsic influences (such as cultural difference, insufficient, or inappropriate instruction), but are not the result of these conditions or influences" (Bunch & Melynk, 1989, p. 298).

Educators question whether deaf and hard of hearing students are eligible to be classified as learning disabled and receive special education services based on this condition (Bunch & Melnky, 1989; LaSasso, 1985). As a result, the National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (NJCLD) revised the definition to remove the federal barrier to developing services for deaf and hard of hearing students with learning disabilities in the school system. "Learning disabilities" are defined by the NJCLD as "conditions or influences that occur concurrently with other handicaps (for example, sensory impairment, mental retardation, or serious emotional disturbance) or extrinsic influences (such as cultural difference, insufficient, or inappropriate instruction), but are not the result of these conditions or influences" (Bunch & Melynk, 1989, p. 298).

The federal definition states that "there are no... hearing impaired learning disabled children in the world—the idiocy of such a rule denies the evidence" (Sabatino, 1983, p. 26). The definition of learning disabilities was also criticized by Hammill, Leigh, McNutt, and Larsen (1981). They conclude that it is a misconception that learning disabilities cannot occur in the presence of other handicapping conditions or environmental, cultural, or economic advantages.

I beg to differ, as I mentioned in my "Tearing Down the Wall" story. Regardless of the issue with the "legal" definition of learning disabilities, qualified professionals should classify deaf and hard-of-hearing students as learning disabled if they have identified learning disabilities. I am convinced that there are deaf and hard of hearing students with learning disabilities. They are entitled to be classified as having learning disabilities and to receive appropriate services from secondary and postsecondary institutions. After all, I am living proof of the situation.

LEAD-K: Food for Thought

@http://www.cad1906.org

@http://www.cad1906.org

The Language Equality and Acquisition for Deaf Kids (LEAD-K) program advocates for deaf and hard of hearing children to have equal access to language acquisition and literacy before they are academically ready for kindergarten. It became law or policy in an increasing number of states.

To give a brief overview, LEAD-K requires all deaf and hard of hearing babies to undergo language acquisition assessments every six months until they reach the age of five. However, unless one of their parents has dyslexia or a visual processing disorder, detecting those with dyslexia or a visual processing disorder during the first five years may be difficult.

If you notice a student with a learning disability exhibiting any characteristics that are not typically seen with a hearing loss, we should be on the lookout for dyslexia or visual processing issues. As stated in the "Our D/LD Journey" section, you may want to ask the child to describe their reading difficulties and see if their symptoms are consistent with dyslexia or visual perception issues. Dyslexia and difficulties with visual processing are not the same thing. Let's look at the chart that shows the distinction between them. Looking back, I wish I had received more information about dyslexia and visual processing issues and their effects on academic advancement. I regret not providing DJK with early reading intervention.

While identifying the capacities and limitations of perception processing issues, educators should keep dyslexia and eight types of visual processing issues in mind. It may aid in the detection of early reading problems in deaf and hard of hearing children.

To give a brief overview, LEAD-K requires all deaf and hard of hearing babies to undergo language acquisition assessments every six months until they reach the age of five. However, unless one of their parents has dyslexia or a visual processing disorder, detecting those with dyslexia or a visual processing disorder during the first five years may be difficult.

If you notice a student with a learning disability exhibiting any characteristics that are not typically seen with a hearing loss, we should be on the lookout for dyslexia or visual processing issues. As stated in the "Our D/LD Journey" section, you may want to ask the child to describe their reading difficulties and see if their symptoms are consistent with dyslexia or visual perception issues. Dyslexia and difficulties with visual processing are not the same thing. Let's look at the chart that shows the distinction between them. Looking back, I wish I had received more information about dyslexia and visual processing issues and their effects on academic advancement. I regret not providing DJK with early reading intervention.

While identifying the capacities and limitations of perception processing issues, educators should keep dyslexia and eight types of visual processing issues in mind. It may aid in the detection of early reading problems in deaf and hard of hearing children.

Language Deprivation and Deaf Mental Health

Many of you are probably aware that a book titled "Language Deprivation and Deaf Mental Health" has recently been published and has raised awareness in the Deaf community. For years, I've wondered if a deaf person's literacy difficulties are caused by language deprivation or a learning disability. Of course, we can easily associate this area with deaf children raised by deaf parents. The majority of deaf children, however, are born to hearing parents. This gray area makes it difficult for an evaluator to identify a child with a learning disability in reading or writing. As a result, they are frequently misdiagnosed when they should be associated with language deprivation syndrome.

In 2018, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) released its "priority proposals," which NAD members voted on to determine their immediate priorities. One of the suggestions was to include language deprivation syndrome (LDS) in both ICD-10 and DSM-5 (proposed by Mickey Morales). Of course, as a former NAD member, I voted favorably. It did not, however, make the top five priorities. We need to push for it to happen. It will help in identifying the commonly misunderstood diagnostic categories before providing services. I often work with deaf college students who are not fluent in English, and retention has been challenging. If they are diagnosed with language deprivation syndrome, we can provide the accommodations and support they need to succeed. It is the most overlooked but crucial area.

In 2018, the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) released its "priority proposals," which NAD members voted on to determine their immediate priorities. One of the suggestions was to include language deprivation syndrome (LDS) in both ICD-10 and DSM-5 (proposed by Mickey Morales). Of course, as a former NAD member, I voted favorably. It did not, however, make the top five priorities. We need to push for it to happen. It will help in identifying the commonly misunderstood diagnostic categories before providing services. I often work with deaf college students who are not fluent in English, and retention has been challenging. If they are diagnosed with language deprivation syndrome, we can provide the accommodations and support they need to succeed. It is the most overlooked but crucial area.

References

Bunch, G.O. & Melnyk, T.L., (1989). A review of the evidence for a learning disabled, hearing-impaired sub-group. American Annals of the Deaf, 134(5), 297-300.

Hammill, D. D., Leigh, J.E., McHutt, G., & Larsen, S.C. (1981). A new definition of learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 4,336-342.

Kachman, W. (1999). Identifying learning disabilities in deaf and hard of hearing college students. Conference Proceeding Bridge the Gap Between Research and Practice in the Fields of Learning Disabilities and Deafness, Washington, D.C. (35-43).

LaSasso, C. (1985). Learning disabilities: Let’s be careful before labeling deaf children. Perspectives, 3(5), 2-4.

Morgan, A. & Vernon, M. (1994). A guide in the diagnosis of learning disabilities in deaf and hard-of-hearing children and adults. American Annals of the Deaf, 139, (3), 358-370.

Plapinger, D., & Sikora, D. (1990). Diagnosing a learning disability in a hearing-impaired child: A study case. American Annals of the Deaf, 135(4), 285-292.

Rush, P. & Baechle, C. (1992). Learning disabilities and deafness: An emergency field. Gallaudet Today, 22(3), 20-26.

Sabatino, D. (1983). The house that Jack built. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 16, 26-27.

Bunch, G.O. & Melnyk, T.L., (1989). A review of the evidence for a learning disabled, hearing-impaired sub-group. American Annals of the Deaf, 134(5), 297-300.

Hammill, D. D., Leigh, J.E., McHutt, G., & Larsen, S.C. (1981). A new definition of learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 4,336-342.

Kachman, W. (1999). Identifying learning disabilities in deaf and hard of hearing college students. Conference Proceeding Bridge the Gap Between Research and Practice in the Fields of Learning Disabilities and Deafness, Washington, D.C. (35-43).

LaSasso, C. (1985). Learning disabilities: Let’s be careful before labeling deaf children. Perspectives, 3(5), 2-4.

Morgan, A. & Vernon, M. (1994). A guide in the diagnosis of learning disabilities in deaf and hard-of-hearing children and adults. American Annals of the Deaf, 139, (3), 358-370.

Plapinger, D., & Sikora, D. (1990). Diagnosing a learning disability in a hearing-impaired child: A study case. American Annals of the Deaf, 135(4), 285-292.

Rush, P. & Baechle, C. (1992). Learning disabilities and deafness: An emergency field. Gallaudet Today, 22(3), 20-26.

Sabatino, D. (1983). The house that Jack built. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 16, 26-27.